I love the segment about magnetic “domains”. Rule with an “iron fist”. Two of my favourite Youtube channels worked together to make this video.

Since almost every student owns a smartphone in SIngapore now, it has become possible for us to gather instant feedback or conduct an on-the-spot formative assessment to identify common misconceptions during class time.

A simple true-and-false quiz conducted during my recent lesson on Gravitation, after the lecture series was completed, showed that students are confused about the different treatment between vectors (force and field strength) and scalars (potential and potential energy).

The questions asked, along with the percentage answered correctly, were:

- If you were sitting half as far from your nearest classmate, the gravitational force of attraction between the two of you would be four times as strong. (81.0% correct)

- At the midpoint of the distance from the center of the earth to the center of the moon, the gravitational field strength is zero. (90.5% correct)

- At the midpoint of the distance between two identical masses, the gravitational potential is zero. (23.8% correct)

- Work done by gravitational force in bringing an object from infinity to the surface of a planet is negative. (38.1% correct)

- Satellites in a geostationary orbit must move directly above the equator. (52.4% correct)

This quiz was effective in helping students realise that potential cannot cancel out.

I also took the opportunity to explain to the class why the definition of gravitational potential (as well as potential energy) was based on the work done by an external force, rather than work done by gravitational force.

The tool that I used was Socrative and if anyone would like to use my quiz, you can follow the steps below:

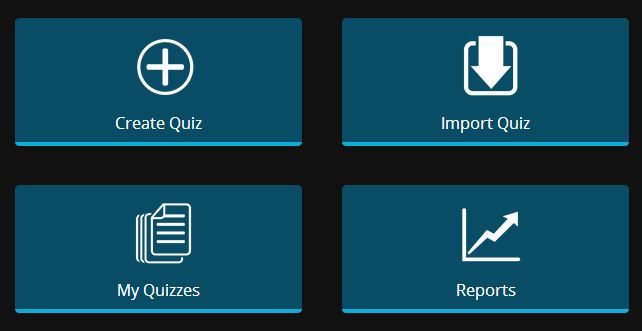

- Create a teacher account (not a student account) at socrative.com and log in.

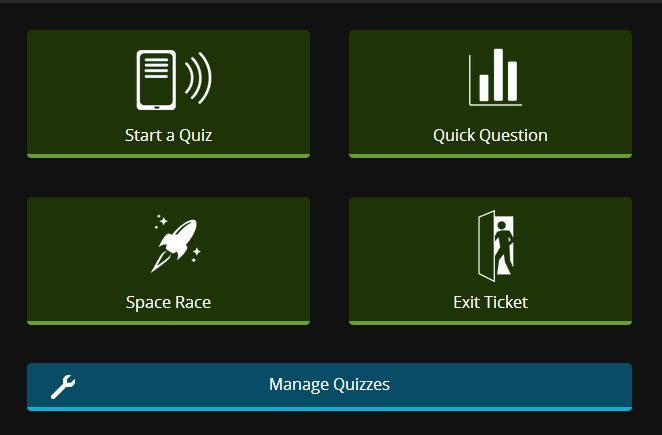

- Click on Manage Quizzes.

-

Key in the SOC number 12289667

Since you have imported the quiz, you have effectively duplicated the quiz for yourself and are at liberty to edit the questions or even modify the quiz altogether as it does not affect mine.

To conduct the quiz, all you need to do is to go back to the dashboard and click on “Start a Quiz”, selecting the quiz you have saved. Follow the rest of the instructions to select the type of quiz you want (whether at students’ own pace or at a pace determined by yourself).

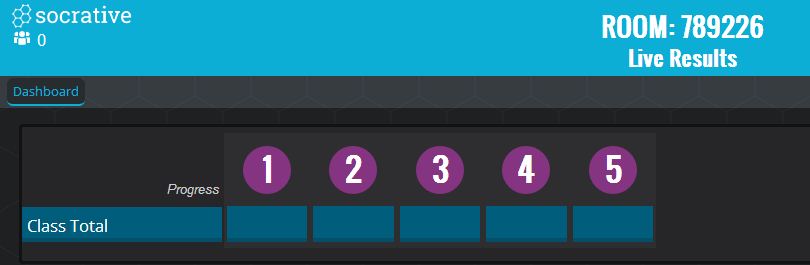

Once you have started the quiz, get your students to log in at m.socrative.com on their smartphone browsers and key in your Room Number (shown at the top of the screen). You will be able to see the number of students logging in at the top left corner and the attempts of your students in the main area.

If you have any questions regarding the use of Socrative in teaching, feel free to leave a comment below and I’ll try to answer it. Have fun!

This video shows yet another demonstration for the effect of resonance, when the sound frequency is equal to the natural frequency of the glass. I have yet to conduct this demonstration because of the potential risks involving flying pieces of glass. A video should suffice though, especially one that is taken at slow motion.

This is a video that we usually will show during a lecture on the topic of Resonance, under the unit “Oscillations”. It was taken in 1940 at the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington, USA. One of the main reasons (not the only reason – the other being aeroelastic flutter) for its collapse is the effect of resonance, which occurs when the driving frequency of the wind that hits the bridge matches the natural frequency of vibration of the bridge.

Witness the freezing and boiling of a liquid take place at the same time. A thorough explanation for this observation is found here.

Cyclohexane can both freeze and boil simultaneously under specific conditions when it is in a state known as triple point.

The triple point of a substance is the unique combination of temperature and pressure where all three phases (solid, liquid, and gas) coexist in equilibrium. For cyclohexane, at its triple point:

- Temperature: Around 6.5°C

- Pressure: Around 0.053 atm (40 mm Hg)

At this point, cyclohexane can freeze (turn from liquid to solid) and boil (turn from liquid to gas) simultaneously. This occurs because the conditions allow the substance to transition between all three phases at the same time. The energy added or removed from the system can cause some molecules to leave the liquid phase as a gas (boiling), while others enter the solid phase (freezing).

Students are sometimes unclear about which of the equations taught in the topic of Thermal Physics apply to ideal gases and which apply to all systems (whether ideal or real gas, even liquids and solid). The following table should help to clarify:

| Applies to Ideal Gas only | Applies to all systems | |

| Gas Laws | ||

| Average Kinetic Energy | $$ |

$$ |

| Internal Energy | ||

| First Law of Thermodynamics | applies to all systems |